Being a New College Graduate Means You are…

April 2, 2014 Leave a comment

Facing an unprecedented amount of debt – According to The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS) Project on Student Debt two-thirds of the graduating class have debt waiting for them at door after graduation with the average borrower graduating approximately $26,600 in the red. In total, student loan debt is amounting to over $1 trillion. $1.2 trillion to be more specific. Think of that number for our new graduates entering the workforce and the economy as a whole. Of this $1.2 trillion in student debt, about $1 trillion is in federal student loans. This figure does not tell the full story, however, as the $1.2 trillion does not include funds students must divert away from retirement savings, parent borrowing, or credit card debt. While a tie for federal student loan interest rates to the market is of some help, lowering the current rates for undergraduate students from 6.8 to 3.8%. But if and as the market climb, these rates will also climb until they reach a cap of 8.25%. By TICAS calculation, this may cost families $715 million more over the next 10 years.

What does the lower number of 3.8% interest actually translate to for students? If we go back to that average figure of $26,600, compounding for interest year over year using the 10-year-payback plan that is the standard, the total cost of your $26,600 loan is now closer to $40,000. Break that down by monthly payments and you are looking at about $320 per month going toward student loan payments. In the end, the opportunity cost of the education itself is almost $40,000 in addition to what’s already been out of pocket for tuition, room, board, books, food, etc. Every dollar now owed is a dollar delayed in terms of the down payment on a house. Money put aside for retirement or investments. Dollars sacrificed for the next generation’s needs.

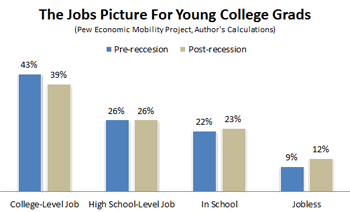

Facing an improved economy but – for every position offered by an employer, not only are the new grads in competition with each other, but facing increasing numbers from laid-off, displaced and/or career changing job-seekers that, in addition to a college degree, offer a tangible employment history and applied experience. With that new competition, increasing numbers of recent college graduates are ending up in relatively low-skilled jobs that, historically, have gone to those with lower levels of educational attainment. This is having a push-down effect where those with only a high-school degree are now being displaced by college graduates.

In fact, the proportion of ‘over-educated’ workers in occupations appears to have grown substantially; for example in 1970, fewer than one percent of taxi drivers and two percent of firefighters had college degrees, while now more than 15 percent do in both jobs; The figures are based on an analysis of the 2011 Current Population Survey data by Northeastern University researchers. They rely on Labor Department assessments of the level of education required to do the job in 900-plus U.S. occupations, which were used to calculate the shares of young adults with bachelor’s degrees who were “underemployed.”

About 1.5 million, or 53.6 percent, of bachelor’s degree-holders under the age of 25 last year were jobless or underemployed, the highest share in well over a decade. In 2000, the share was at a low of 41 percent, and this was when the dot-com bust erased job gains for college graduates in the telecommunications and IT fields. The result is that if you look at employment broken down by occupation, young college graduates were heavily represented in jobs that merely require a high school diploma or even less. The barista serving you coffee with the Ph.D is no longer an urban myth.

Faced with ‘new’ employer skepticism – As more and more news reports and pundits attempt to explain the plight of current prospects for new graduates, another, new-ish court is being heard from more and more; the employers. They say that college students, in general, are entering the workforce, or trying to, with a double whammy working against them; coming in the door without the skills needed to hold down or perform a job AND, in addition, unrealistic expectations about the job itself and the requirements the employer is needing. This means that in a soft job market like we’re now experiencing, recent graduates are facing not only stiff and varied competition from experienced workers re-entering the workforce but also new, budding skepticism from the employers with the (limited) jobs on offer.

According to Inside Higher Ed, more students have struggled to make their mark in a depressed job market and this has raised the obligatory questions about the intrinsic employment value of a college degree? In the same correlative breath has the concern that new graduates are not equipped to function in the work place and are not meeting employers’ expectations and needs. A new survey reaffirms that quandary. In the report, “Bridge That Gap: Analyzing the Student Skill Index,” only half of college students said they felt very or completely prepared for a job related to their field of study. In contrast, and perhaps even more telling, even fewer employers – 39 percent of those surveyed – said the same about the recent graduates they’d interviewed in the past two years. The fact of the matter is that the latter percentage, whether real or perceived, is the benchmark as they, the employers, are the ones hiring.

The most ‘educated’ but the least well prepared – As the more scrutinizing lens of a poor economy starts to look for answers, many have argued that colleges and universities aren’t doing enough to prepare their students for the work force. This is true; sort of… I would have to agree with that assessment and I don’t mean in a way that condemns the educational institutions’ intentions. The problem is that the ‘system’ is not built where the idea of higher education and its synthesis of development and ’employ-ability’ are best intertwined. In most cases, for example, representative career service offices tend to be an isolated campus entity. Either an overbooked office that doesn’t have the resources and staff time to effectively work with students navigating their career path OR an office that can go underutilized or flat-out ignored by the campus community. I’ve seen and experienced both and both are a disservice to the very client’s they try to serve. In the past couple weeks I have spoken with several soon-to-be graduates and the common question asked is “have you been to your campus career center?” Invariably, the answer seems to be either ‘no’ or ‘yes, but only one or two times.’

What’s missing is that colleges need to be systemically embedding career development into the fabric of the undergraduate education. This is a difficult task as many a faculty department will fight the ‘vocation’ label and/or expectation tooth & nail. This is changing as new members replace the incumbents understanding the new economy and its demands but it is a slow evolution at best. If this were to come to fruition, an organic and institutional embedding of course and career, not only would this better prepare students for life after college, it would help to justify the value of a liberal arts degree, or any degree for that matter especially as outcomes are becoming the new quantitative rage.

To qualify, this post is not meant to simply and merely highlight the negatives facing our soon-to-be-freed graduating class, but instead to shed some light on the realities being faced, not just by the current generation, but all generations as there is a systemic, ripple-effect that reaches out and affects us all.

Please Share Us!