Hiring Hurdles: Employer Drug Testing

March 31, 2016 Leave a comment

SAVANNAH, GA. — A few years back, the heavy-equipment manufacturer JCB held a job fair in the glass foyer of its sprawling headquarters near here, but when a throng of prospective employees learned the next step would be drug testing, an alarming thing happened: About half of them left.

SAVANNAH, GA. — A few years back, the heavy-equipment manufacturer JCB held a job fair in the glass foyer of its sprawling headquarters near here, but when a throng of prospective employees learned the next step would be drug testing, an alarming thing happened: About half of them left.

That story still circulates within the business community of this historic port city. But the problem has gotten worse.

All over the country, employers say they see a disturbing downside of tighter labor markets as they try to rebuild from the worst recession since the Depression: They are struggling to find workers who can pass a pre-employment drug test.

That hurdle partly stems from the growing ubiquity of drug testing, at corporations with big human resources departments, in industries like trucking where testing is mandated by federal law for safety reasons, and increasingly at smaller companies.

But data suggest employers’ difficulties also reflect an increase in the use of drugs, especially marijuana — employers’ main gripe — and also heroin and other opioid drugs much in the news.

Ray Gaster, the owner of lumber yards on both sides of the Georgia-South Carolina border, recently joined friends at a retreat in Alabama to swap business talk. The big topic? Drug tests.

“They were complaining about trying to find drivers, or finding people, who are drug-free and can do some of the jobs that they have,” Mr. Gaster said. He shared their concern.

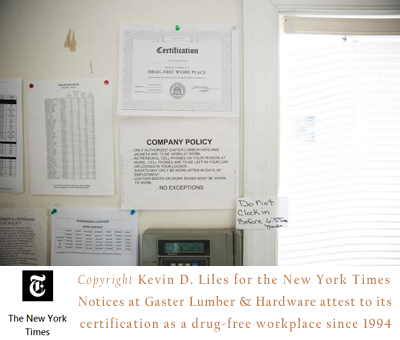

Notices at Gaster Lumber & Hardware attest to its certification as a drug-free workplace since 1994. Drug use in the work force “is not a new problem. Back in the ’80s, it was pretty bad, and we brought it down,” said Calvina L. Fay, executive director of the Drug Free America Foundation. But, she added, “we’ve seen it edging back up some,” and increasingly, both employers and industry associations “have expressed exasperation.”

Notices at Gaster Lumber & Hardware attest to its certification as a drug-free workplace since 1994. Drug use in the work force “is not a new problem. Back in the ’80s, it was pretty bad, and we brought it down,” said Calvina L. Fay, executive director of the Drug Free America Foundation. But, she added, “we’ve seen it edging back up some,” and increasingly, both employers and industry associations “have expressed exasperation.”

Data on the scope of the problem is sketchy because figures on job applicants who test positive for drugs miss the many people who simply skip tests they cannot pass.

Nonetheless, in its most recent report, Quest Diagnostics, which has compiled employer-testing data since 1988, documented an increase for a second consecutive year in the percentage of Americans who tested positive for illicit drugs — to 4.7 percent in 2014 from 4.3 percent in 2013. And 2013 was the first year in a decade to show an increase.

John Sambdman, who employs about 100 people in Atlanta at Samson Trailways, which provides transportation for schools, events, tour groups and the military, must test job applicants and, randomly, employees. Many job seekers “just don’t bother to show up at the drug-testing place,” he complained. Just on Thursday, Mr. Sambdman said, an applicant failed a drug test.

In August, Gov. Nathan Deal of Georgia promised to develop a program to help because so many business owners tell him “the No. 1 reason they can’t hire enough workers is they can’t find enough people to pass a drug test.”

That program is still under discussion. When job seekers contact Georgia’s Department of Labor, which provides some recruitment services to employers, the state would like to begin testing them for drugs; individuals who test positive could receive drug counseling and ultimately job placement assistance, Mark Butler, the state labor commissioner, said in an interview.

“Obviously, it’s not an easy process, and it would be costly,” Mr. Butler said. “But you’ve got to think: What is the reverse of that?” People needed to fill jobs are turned away, and, he added, “it’s pretty much a national issue.”

In Indiana, Mark Dobson, president of the Economic Development Corporation of Elkhart County, said that when he went to national conferences, the topic was “such a common thread of conversation – whether it’s in an area like ours that’s really enjoying very low unemployment levels or even areas with more moderate employment bases.”

In Colorado, “to find a roofer or a painter that can pass a drug test is unheard-of,” said Jesse Russow, owner of Avalanche Roofing & Exteriors, in Colorado Springs. That was true even before Colorado, like a few other states, made recreational use of marijuana legal.

In a sector where employers like himself tend to rely on Latino workers, Mr. Russow tried to diversify three years ago by recruiting white workers, vetting about 80 people. But, he said, “As soon as I say ‘criminal background check,’ ‘drug test,’ they’re out the door.”

While employers’ predicament is worsened by a smaller hiring pool, the drug problem for those that require testing is not as bad as it once was. “If we go back to 1988, the combined U.S. work force positivity was 13.6 percent when drug testing was new,” said Dr. Barry Sample, Quest’s director of science and technology.

But two consecutive years of increases are worrisome, he said.

A much broader data trove, the federal government’s annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, reported in September that one in 10 Americans ages 12 and older reported in 2014 that they had used illicit drugs within the last month — the largest share since 2001.

Taken together, Mr. Sample said, his data and the government’s indicate higher drug use among those who work for employers without a drug-testing program than workers who are tested, though use by the latter increased as well in 2013 and 2014.

Testing dates to the Reagan administration. The 1988 Drug-Free Workplace Act required most employers with federal contracts or grants to test workers. In 1991, Congress responded to a deadly 1987 train crash in which two operators tested positive for marijuana by requiring testing for all “safety sensitive” jobs regulated by the Transportation Department. Those laws became the model for other employers. Some states give businesses a break on workers’ compensation insurance if they are certified as drug-free.

Here at the main yard of Gaster Lumber and Hardware, faded certificates and signs (“Drugs Don’t Work Here”) attest to its certification as a drug-free workplace since 1994.

Mr. Gaster’s human resources director, Chuck Keller, said that status reduced workers’ compensation payments for its nearly 50 employees by 7.5 percent in Georgia and 5 percent in South Carolina. The savings, about $4,000 this year, offset costs of about $2,500 for laboratory and on-site testing and related requirements.

“We’re always short of drivers,” Mr. Gaster said, “and drug testing is part of it.”

Terry Donaldson, 53, who was tested when he started 20 years ago, supports the policy: “If they want to have a good job, the drugs got to go.”

So it was for some of his new co-workers.

Britt Sikes, 38 and a single father to three young girls, lost his teeth to methamphetamine and used marijuana since he was 8 — until three weeks before taking the test for his $13-an-hour job as a Gaster door installer.

“I’m a recovering drug addict myself, and to raise my girls, I had to learn to leave it alone,” Mr. Sikes said.

Kevin Canty, 55, said that in his experience, “most people can’t pass the drug test because they don’t want to pass a drug test.”

“They want the job,” he added, but “they still want to be in that lifestyle. And they have to choose.”

One of the newest hires, Frederick Brown, 34, said, “I come from a society where drugs is common – marijuana, weed, it’s common,” and people who cannot pass a drug test seek work at McDonald’s. Most restaurants do not test.

“I asked for this job,” Mr. Brown said, calling it a blessing. “I already knew what I had to do — you know what I’m saying?”

Please Share Us!